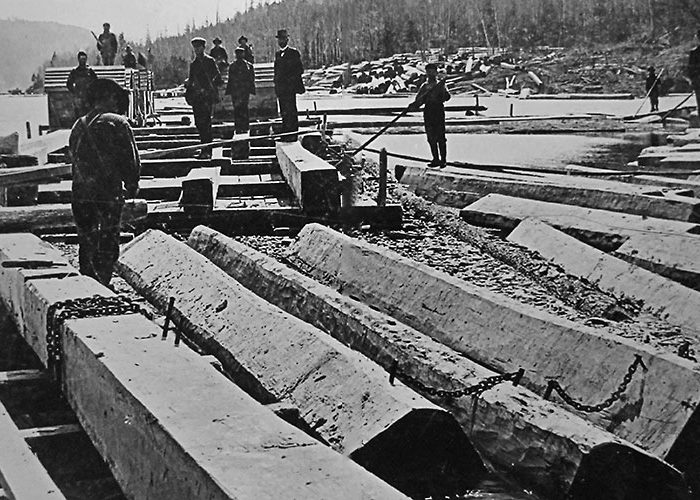

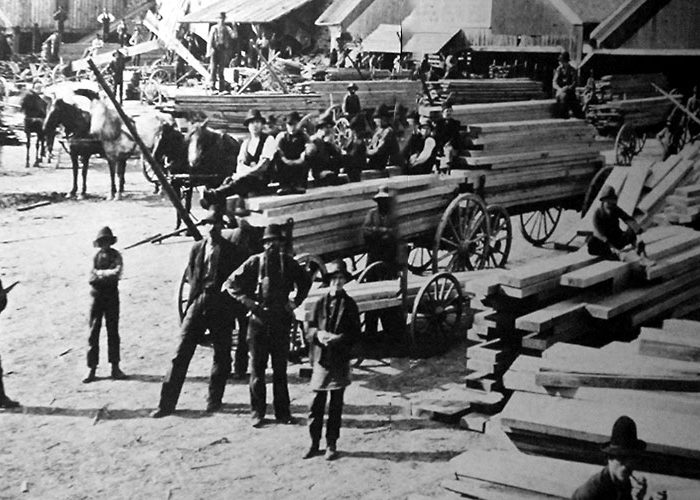

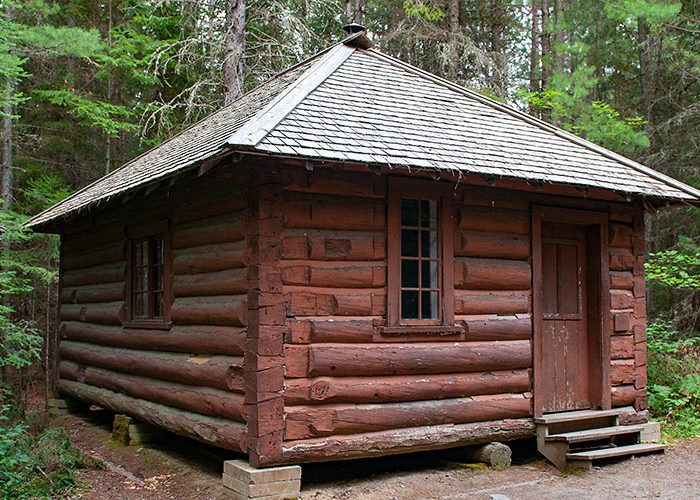

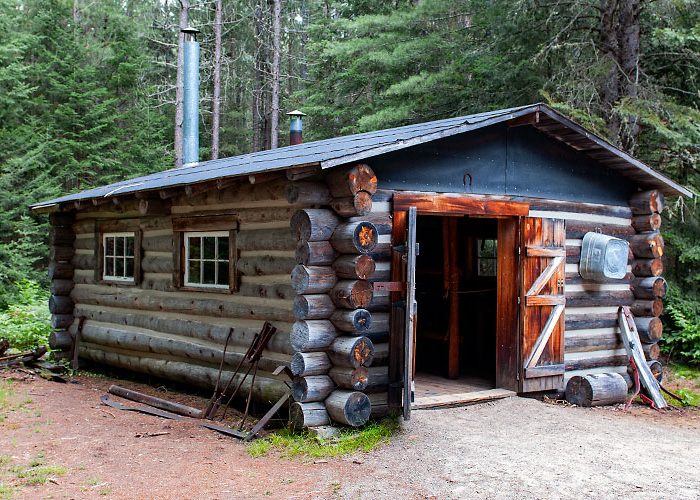

Take a step back in time and learn about this very colourful aspect of Algonquin’s cultural history. The Algonquin Logging Museum brings to life the story of logging from the early square timber days to modern forestry management.

On the easy-to-walk 1.5 km trail, a recreated camboose camp and a fascinating steam-powered amphibious tug called an “alligator” are among the many displays.

Logging for square timber (white and red pine) began about 1830 when James Wadsworth obtained a timber licence to cut red pine from Round Lake to the source of the Bonnechere River.

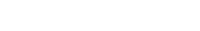

In 1846, 141,600 cubic metres of red and white pine were harvested and floated down the Madawaska, Bonnechere, and Petawawa Rivers. Peak of the square timber trade was reached in 1864 and the last square timber was cut near the Petawawa River north of Brûlé Lake in 1912.

And today?

Did you know Algonquin Park is the only Ontario provincial park not protected from logging? In fact, 65 per cent of the park is open to commercial logging, putting ecosystems and biodiversity at risk. Industrial logging in Algonquin Provincial Park is a bad habit of the past and should be banned. Algonquin is valued as a place to connect with nature and a refuge for wildlife and plants. Logging is an assault on these values and contrary to the reason provincial parks were created — in a time of mounting threats to biodiversity it is time to add to Ontario’s protected system and give Algonquin the full and real protection it deserves.

Book to read: John Irving / Last Night in Twisted River

“The young Canadian, who could not have been more than fifteen, had hesitated too long.”

So begins John Irving’s twelfth novel, Last Night in Twisted River. In 1954, in the cookhouse of a logging and sawmill settlement in northern New Hampshire, an anxious twelve-year-old boy mistakes the local constable’s wife for a bear. Both the twelve-year-old and his father become fugitives, forced to run from Coos County—to Boston, to southern Vermont, to Toronto—pursued by the implacable constable.

Their lone protector is a fiercely libertarian logger, once a river driver, who befriends them. In a story spanning five decades, Last Night in Twisted River depicts the recent half-century in the United States as “a living replica of Coos County, where lethal hatreds were generally permitted to run their course.”

The young Canadian, who could not have been more than fifteen, had hesitated too long. For a frozen moment, his feet had stopped moving on the floating logs in the basin above the river bend; he’d slipped entirely underwater before anyone could grab his outstretched hand. One of the loggers had reached for the youth’s long hair—the older man’s fingers groped around in the frigid water, which was thick, almost soupy, with sloughed-off slabs of bark. Then two logs collided hard on the would-be rescuers arm, breaking his wrist. The carpet of moving logs had completely closed over the young Canadian, who never surfaced; not even a hand or one of his boots broke out of the brown water.

Out on a logjam, once the key log was pried loose, the river drivers had to move quickly and continually; if they paused for even a second or two, they would be pitched into the torrent. In a river drive, death among moving logs could occur from a crushing injury, before you had a chance to drown—but drowning was more common.

From the riverbank, where the cook and his twelve-year-old son could hear the cursing of the logger whose wrist had been broken, it was immediately apparent that someone was in more serious trouble than the would-be rescuer, who’d freed his injured arm and had managed to regain his footing on the flowing logs. His fellow river drivers ignored him; they moved with small, rapid steps toward shore, calling out the lost boy’s name. The loggers ceaselessly prodded with their pike poles, directing the floating logs ahead of them. The rivermen were, for the most part, picking the safest way ashore, but to the cook’s hopeful son it seemed that they might have been trying to create a gap of sufficient width for the young Canadian to emerge. In truth, there were now only intermittent gaps between the logs. The boy who’d told them his name was “Angel Pope, from Toronto,” was that quickly gone.

Algonquin Logging Museum Original website