Grey Owl / Wa-sha-quon-asin (1888 – 1938) was the most famous Canadian Indian in the world in the 1930s. He wanted to protect the forests and animals of Canada. But Grey Owl also had a big secret.

Grey Owl looked and acted like an Indian, but he also spoke and wrote English well. His life was mystery, but most people remember Grey Owl for his message: that if we do not look after the natural world, we will lose it.

Man should enter the woods, not with any conquistador obsession or mighty hunter complex, neither in a spirit of braggadocio, but rather with … awe …. For many a man who considers himself the master of all he surveys would do well, when setting foot in the forest, to take off not only his hat but his shoes too and, in not a few cases, be glad he is allowed to retain an erect position.

(Grey Owl, 1936)

At the time that Archie Belaney was born, there was growing interest in Native Americans and their disappearing lifestyle.

The romantic idea of the brave American Indian, described in Fenimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans (1826), was a popular one, and young Archie became entranced by it. He was also a fan of Longfellow’s famous poem The Song of Hiawatha (1855), which reproduces traditional American Indian stories.

His main concerns were the dwindling numbers of some varieties of animals and types of tree. He was largely responsible for building up a new population of beavers in the Riding Mountain National Park, where trapping had decimated their numbers.

People are divided about Archie. Most of those who have read his books think he did more good than harm and admire him as a pioneering conservationist. Others who focus on his terrible treatment of his wives and children and his lies find it more difficult to treat him as a hero.

Grey Owl’s writings gave the world an important vision of Canada’s northern wilderness and provoked the debate between using land and conserving it that continues today. He described it as a “land of shadows and hidden trails, lost rivers and unknown lakes, a region of soft-footed creatures”.

(The Passing of the Last Frontier”, Country Life, March 2, 1929)

His real name was Archie Belaney.

Before Archie was born, his British parents, George and Kitty, worked in America but did not make much money. They returned to England and lived with George’s mother. There Archie was born. Then George returned to America and Archie went to live with his aunts. As a boy, Archie had few friends but he loved animals and read about Indians. He hated school so he left and went to work in an office, but he didn’t like office work either.

When Archie was seventeen, he left his boring office job and sailed off to Canada. After working for a few months in Toronto, he travelled north and met Bill Guppy. Bill taught Archie to trap animals and helped him get a job at a hotel on Lake Temagami. He began to learn about the Ojibwa Indians who lived on an island in the lake. The Ojibwa taught Archie their ideas about life and nature.

Archie went back to England in 1907, but he soon returned to Lake Temagami. He lived with the Ojibwa tribe around the Great Lakes and learned the ways of the forest.

He married an Ojibwa woman, Angele, and began to spend most of his time with Indians. He wore Indian clothes and acted like an Indian.

In 1912, while he was living in the town of Bisco and in 1915, Archie joined the Canadian Army. He went to Europe and fought in the First World War. He was shot and sent back to England. The war affected him deeply.

When Archie returned to the America. he stayed in Bisco and met an Indian named Alex, and his family, who became an important part of his life. At this time, Archie was writing stories and drawing in a notebook. He began to dress and act like an Indian again. He returned to Lake Temagami.

The name Belaney claimed to have received throgh this ritual was:

Wa-sha-quon-asin / Grey Owl.

A blood-brother proved and sworn, by moose-head feast, wordless chant, and ancient ritual was I named before a gaily decorated and attentive concourse … The smoke hung in the white pall short of the spreading limbs of the towering trees, and with a hundred pairs of beady eyes upon me I stepped out beneath it when called on … Hi-Heeh, Hi-Heh, Ho! Hi-Heh, Hi-Heh, Ha! … and there I proudly received the name they had devised (Grey Owl, 1931).

Archie worked in the forests, trapping animals and guiding tourists through the natural environment. In 1925, he began a new life in a cabin in the forest with a young Iroquois Indian called Anahareo. She was shocked by the cruelty of trapping and persuaded Archie to start caring for animals instead of shooting them. They kept orphan beaver kits as companions in their cabin.

In the spring of 1931 a letter arrived from Campbell informing them that Riding Mountain National Park had been selected as the site for the beaver colony and Grey Owl, with Anahareo and Jelly Roll and Rawhide, set off for Manitoba.

Cameramen there made a film entitled The Beaver Family, but Grey Owl was not pleased with the location because it was too dry. He wrote Campbell and the following spring the sanctuary was moved to Prince Albert National Park, sixty miles northwest of Prince Albert to Lake Waskesieu and another thirty miles of portaging to Ajawaan, his home until he died. There he built a log cabin, called it Beaver Lodge. At last he had found his perfect location and, too, he had found the perfect confidant in Major J. A. Wood, superintendent of Prince Albert National Park, who joined in his plans with great enthusiasm. >>

At this time Archie began a new career as a writer. Adopting the name Grey Owl, he wrote articles about nature, animals and Indian life for European magazines. He travelled and gave talks, and wrote three best-selling books. Anahareo had a daughter, but she did not like Grey Owl’s new life and in 1936, she left him.

Grey Owl’s private life was unhappy, but he was becoming a celebrity. In late 1936, he married a French-Canadian woman named Yvonne. The next year, he made a film and planned to make another. He returned to Canada. A newspaper reporter interviewed him and told him he knew about Archie’s secret. The newspaper did not print the story because many people liked Grey Owl’s message.

Man, the beaver, the deer, the hawk —each has his own habits. One is no better than the other but they are different and man’s difference is that he is blessed—or cursed—with imagination. This makes him dream and build castles and see himself as a conquering hero. It even makes him so stupid as to say: “God made man in His own image,” when, actually, and quite obviously, men have made a God in their own image. I am a Neolithic man; I am no sophisticate.

In April 1938, he returned to Beaver Lodge, his cabin at Ajawaan Lake. Five days later, he was found unconscious on the floor of the cabin. Although taken to Prince Albert hospital for treatment. He died of pneumonia on April 13, 1938. He was buried near his cabi

Shortly after his death in April 1938 at his home in Canada, a story appeared in a local newspaper. It said that Grey Owl was English – that he had no Indian blood at all.

Modern influences have taken away much of the romance, picturesque appearance from Indian camps… Their racial pride has been sapped, and destitute and hopeless, they no longer have the ambition to keep up the old methods and traditions, so that home life is slipshod and wretched, and national character is falling into decay

(Grey Owl, 1936)

A movie was made of Grey Owl’s story in 1999, starring Pierce Brosnan as Archie and Annie Galipeau as Anahareo. It was directed by Richard Attenborough. The movie changes the actual story slightly, by revealing Archie’s true identity before his death.

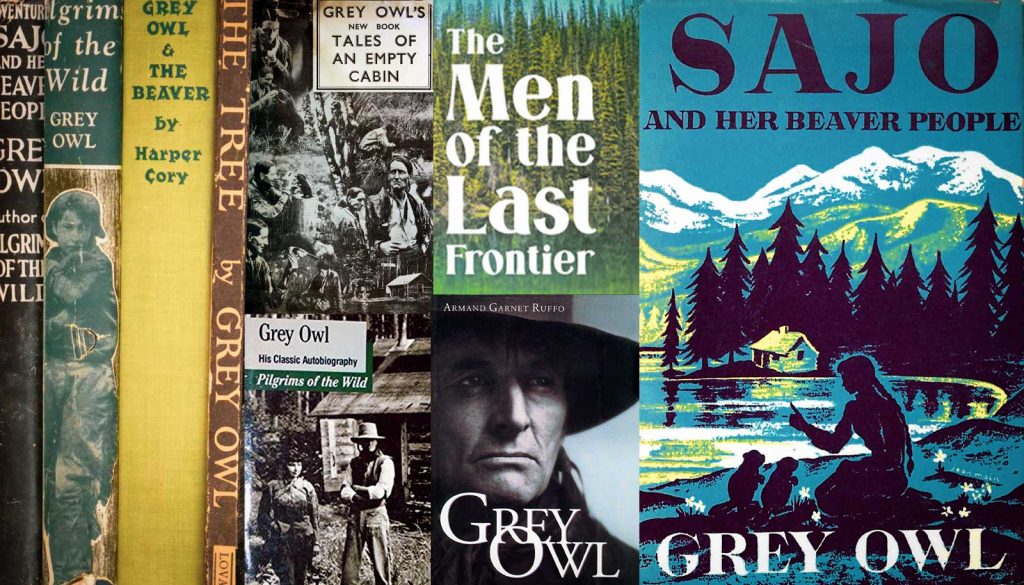

GREY OWL’S BOOKS:

The Men of the Last Frontier, 1931

The Men of the Last Frontier , a work that is part memoir, part history of the vanishing wilderness in Canada, and part compendium of animal and First Nations tales and lore.

Pilgrims of the Wild, 1934

Book is Grey Owl’s autobiographical account of his transition from successful trapper to preservationist. With his Iroquois wife, Anahereo, Grey Owl set out to protect the environment and the endangered beaver. Powerful in its simplicity, Pilgrims of the Wild tells the story of Grey Owl’s life of happy cohabitation with the wild creatures of nature and the healing powers of what he referred to as “the great Northland” of “Over the Hills and Far Away.”

The Adventures of Sajo and her Beaver People, 1935

The ‘beaver people’ are represented in this book by Chilawee and Chikanee, two beaver kittens, whose names mean ‘Big Small’ and ‘Little Small’. Rescued by an Indian hunter after their home dam had been broken by an invading otter, they are taken home to his daughter Sajo and his son Shapian and become the beloved pets of the whole Indian village. Their adventures with the children and their final reunion with the parent beaver make a story that is truly irresistible.

Tales of an Empty Cabin, 1936

Tales of An Empty Cabin is the most beloved collection of stories written by Grey Owl.

Most Important Articles:

In the 1931 Grey Owl wrote many articles for the Canadian Forestry Association (CFA).

King of the Beaver People

A Day in a Hidden Town

A Mess of Pottage

The Perils of Woods Travel

Indian Legends and Lore

A Philosophy of the Wild